This blog was originally featured on the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine’s Maternal Adolescent Reproductive & Child Health Centre Blog.

Dr Hannah Blencowe joined the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) fresh out of working in Malawi as a pediatrician at Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Blantyre where she helped to run the neonatal unit. Having trained in UK hospitals, Hannah was shocked to observe the number of small babies who were being brought to hospital and dying unnecessarily. Even worse, the deaths were in vain with no-one capturing or recording them, just a trail of bereaved mothers who would all too frequently be seen again in the coming years with the same problems.

Knowing that many of these deaths were preventable, and that action could make a difference, Hannah joined LSHTM. Initially as an M.Sc student and then stayed on as staff PhD with the Maternal and Newborn Health group within the MARCH centre at LSHTM. As someone who had always enjoyed counting, her PhD would focus on data collection and analysis.

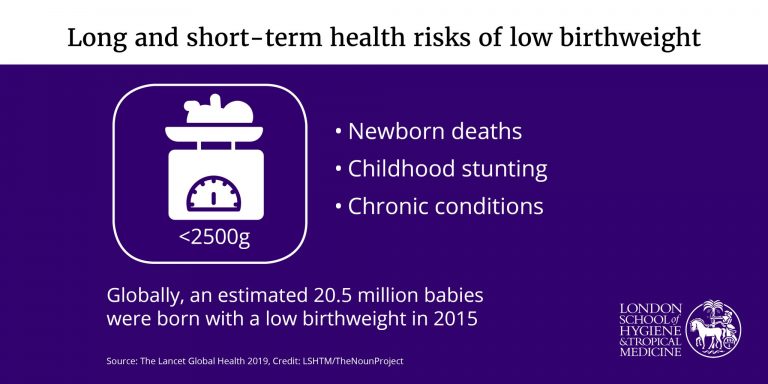

10 years on, Hannah’s work has just been published in the Lancet Global Health – calling attention to, and demanding action for, the 20.5 million low birth weight babies born worldwide in 2015.

I managed to catch Hannah for an interview in the brief respite between submitting her PhD thesis, speaking to journalists, and preparing for her viva. Below is this extraordinary work in her own words…

Q: First, it’d be great to learn a bit more about you. What inspired you to work on maternal and newborn health at LSHTM?

I previously worked in Malawi as a pediatrician, part of my role was working with a team to run the neonatal unit there. There were so many small babies coming in and dying unnecessarily, and I’d come from the UK where those babies wouldn’t have died. Seeing the impact on the mothers, the healthcare staff – the demotivation.

And I realised that these babies counted to their mothers but not to anyone else – the hospitals weren’t interested in them, they weren’t being captured in any kind of data systems, and things weren’t changing. I’d see the same mothers coming back again and again with things that were preventable and we could have done things about. And that made me think: “Where can I start?”.

For me, I’ve always liked counting so data was a natural place to start. I long to see every baby count to their mothers, count to themselves, and also play a part in helping to improve outcomes for the next generation.

Q: And that’s led to the paper that has just been released! If you had to describe the paper in one sentence, what would you say?

That’s a tricky one! So, there were 20.5 million low birth weight babies were born in 2015. And they are at higher risk of dying as babies and as infants, of being stunted, suffering malnutrition as children, and having chronic adult diseases.

Q: Okay – so for my understanding, what exactly do you mean by ‘low birth weight baby’?

It’s any baby born with a birth weight of less than 2.5 kilos. And there are two reasons for this. They’ve either not grown well enough in the womb, that’s called in-uterine growth restriction. Or they’ve not had long enough to grow in the womb and were born before 37 weeks, called preterm birth.

Some babies can actually be both – born early and born small. The term ‘low birth weight’ applies to any baby born less than 2.5kg. Image credit: IDEAS.

Q: You’ve covered this a bit previously, but why is low birth weight a problem? What are the short and long term consequences and why should we care about it?

The short term I’ve already alluded to, these babies need extra care at the time of birth. They’re more likely to get cold, they’re more likely to be unable to feed, they’re more likely to have breathing problems and get infections – particularly if they’re preterm as well. And all of these reasons mean they’re much more likely to die.

For those babies that survive, their small size and difficulty feeding means they’re often stunted and malnourished as a child. This makes them more vulnerable to infections as children as well.

Long term as adults they’re at higher risk of chronic diseases such as hypertension and diabetes. We know the start of health begins in-utero, so if unhealthy at that point, it will lead to longer term problems.

And that’s why it matters for the babies, but it also matters to mums as well. These are mums whose babies may die, or go on to struggle through life. I think quite often we miss the parents out of the picture.

Q: Are there differences in the number of babies born in Low & Middle Income Countries (LMICs) versus High Income Countries (HICs)?

Yes, there are differences. These can be seen in the overall rates – the rates tend to be lower in HICs than LMICs.

The underlying reasons are actually similar in both settings, but each individual country has different risk and balances for how many are preterm, how many are growth restricted, and how many are both. For instance, in South-East Asia there tends to be more babies born on time but who are growth resticted and in Africa there are more preterm babies.

Q: Okay, so what are the underlying causes and are there any notable differences?

It varies across settings but the broad categories are generally the same wherever you are.

There’s maternal infection and that’s more common in areas where there are high levels of malaria, say, or HIV. Areas like Africa, and this drives preterm births.

There are some specific causes related to environmental factors such as smoking and in low income countries indoor air pollution remains an important preventable risk factor for low birthweight

Alternatively you have chronic conditions and that’s universal across the world – maternal hypertension and maternal diabetes.

What’s makes a huge difference in these cases is not the cause but the level of care. Most women in high-income countries can access ante-natal care and they get timely, high-quality care. Because of this the doctors pick up if the mum has an infection, if she has hypertension , if she has diabetes, and they manage her pregnancy accordingly. So the baby grows to the best of it’s ability and it’s born at the time for its optimal health and survival.

That’s not the case in LMICs, where even though women may access ante-natal care at least once in their pregnancy, the quality of care they get is too often really poor. The infections don’t get picked up, the women don’t get diagnosed with hypertension or any other issues – and that’s a big problem.

One of the unspoken, and “taboo” causes is maternal age, so mums who are either very young (under 17), and mums who are older (over 40) are at higher risk of low birthweight babies. And this can be the result of premature birth of growth restriction. In this instance, one of the biggest challenges is access to family planning and empowering women to be able to choose the time they have their babies for optimal health.

Q: When it comes to solving some of these challenges, what kind of changes would you bring about? And would that differ for LMICs vs. HICs?

In high income countries, I would look at the important factors we could do something about. For instance, in some HICs smoking is still a huge problem. And we’ve seen that in countries where we’ve reduced smoking – for instance Scotland – there have been really big reductions in pre-term babies and growth restriction. There are many countries in the east of Europe where smoking is still highly prevalent and acting on that could be an important change at the public health level.

Maternal age is also a big one – we’ve seen a shift up in maternal age across high-income settings, and I don’t think women are always aware of the risks of delaying pregnancies. Having workplace environments that are conducive to having pregnancies at a time that is optimal for maternal health, enabling career progression, and clear routes back into work is really fundamental for HICs.

And a final change for HICs would be medically unnecessary caesarean sections. It’s often the case that in these setting babies are born preterm by caesarean when they needn’t have been – and both mother and baby would have been better if the baby had have stayed inside a bit longer. Women in LMICs need to be empowered through education, access to nutrition, and access to high quality healthcare. Image credit: IDEAS.

For LMICs it’s all about empowerment. I know it sounds really big, but actually, if women can be raised out of poverty, if they can actually have an education and be empowered to make choices about when they get pregnant, if they have knowledge around nutrition and adequate access to nutrition both before and during pregnancy, and finally if we can reduce their exposure to indoor air pollution – then that could improve maternal mental health and well being and make a real difference.

In addition they need access to high quality healthcare, including antenatal care. For women who access this service – they’re making that effort to go, but at the moment they’re all too often not receiving anything that would give them a benefit for themselves or their babies. We need to give them access to greater quality of care.

Q: They’re pretty big challenges and could appear intimidating to tackle. What would you advise anyone reading this to do if they wanted to make a difference?

We need people to advocate in all settings, but particularly for mothers and babies living in LMICs where we know 90% of these babies are born. Raising awareness that this is an important issue is really critical.

For those working in research, ask yourselves the question: “How could I include this if I’m working in the field of maternal and child health? How can I bring this in? How can I raise awareness through my work?”.

Q: If you could only tell people three key messages from this paper, what would they be?

For me, the three key messages are the three key gaps.

Firstly, the data gap. Low birth weights represent a really big global problem, we’re talking 20.5 million babies and their mothers affected in 2015 alone. But the data isn’t always available. Each baby should be weighed so that we can improve their care and improve things for the future as well.

Next is the prevention gap. We are reducing the number of low birth weight babies but slowly. There’s a target of 30% reduction in low birth weight by 2025, which is why we did this work to get some baseline tracking towards that target. But progress has been really slow over the last decade, and if we are to reach that target we need to more than double progress – meaning we need to take action to prevent low birth weight where we can.

Finally, is a care gap. Of these 20.5 million babies, 90% are in LMICs where they’re not getting the care after birth that they need. And I think many of these babies are dying because too often we’re not giving them the care that they need after birth – either on postnatal wards or in neonatal wards, and we’re not giving their mothers enough support to care for their babies once they go home.

Q: And if everything goes to plan with this type of research, where do you hope we’ll be in 10 years’ time?

I’d like to see investment at the critical places – and for me the critical places are antenatal clinics: improving quality of care, and picking up and diagnosing treatable conditions in mothers so that they can improve the outcomes for their babies. I would also like to see investment in newborn inpatient care, and postnatal care, coupled with improved support for mothers caring for these babies, enabling their babies to survive and thrive.

Q: Finally, as I’m writing for the MARCH blog I have to ask: has being a member of MARCH helped with this work?

Yes – being in an environment with loads of inspirational colleagues in the field of maternal and child health is really helpful and gives me drive to keep on going. Its not always easy, when you’ve spent 5 years collating all this data it can be easy to lose sight of the big picture. But being part of the MARCH reminds me that we’re working to ultimately improve the lives of women and children worldwide.

References