This blog was originally published in The Lancet as a commentary here.

By Mija Ververs & Akanksha Arya

This year’s Global Nutrition Cluster meeting in July, 2019, offered a platform on which to discuss all nutrition-related humanitarian emergencies. Ebola virus disease (EVD) and breastfeeding in DR Congo was an obvious topic. More than 2800 cases have been confirmed in the ongoing outbreak in DR Congo; most cases are adults, and 56% of cases are women.1 Ample information is available on the presence of Ebola virus in bodily fluids such as blood, urine, and semen, and on the prevention of transmission from these fluids. However, information on EVD and breastmilk is limited.

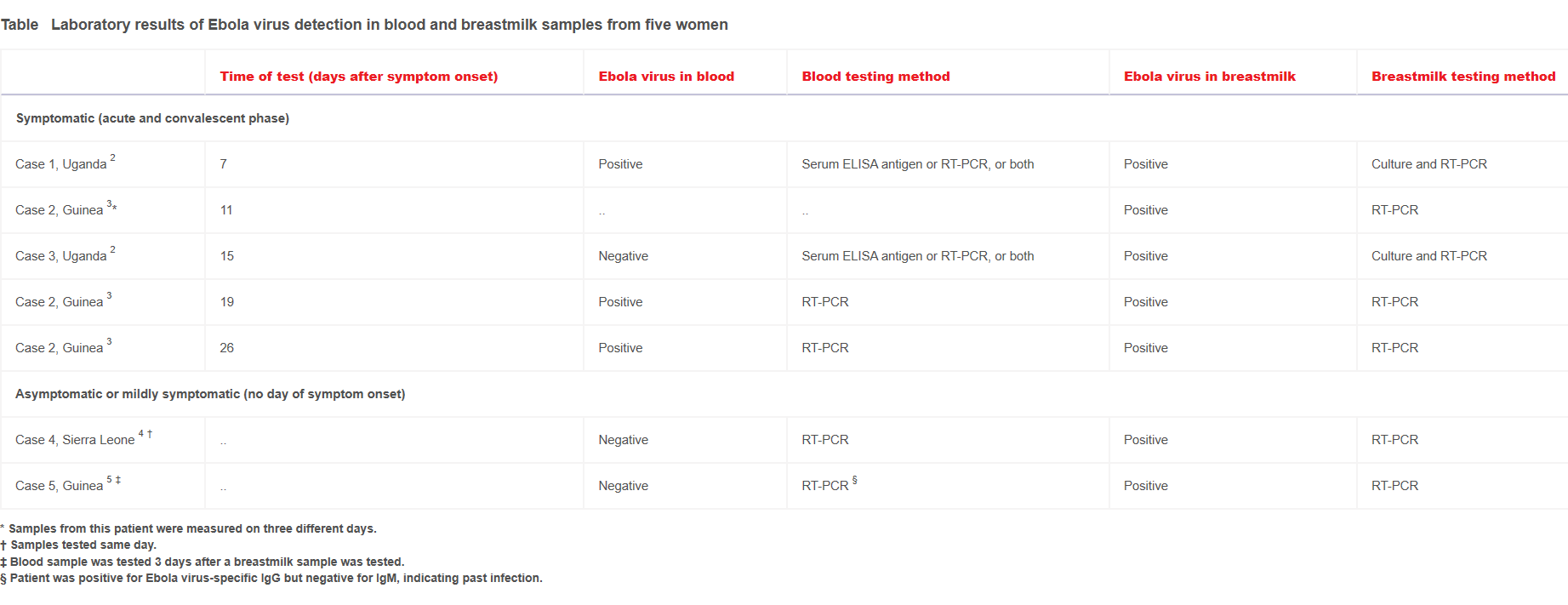

Ebola virus has been found in the breastmilk of mothers in acute and convalescent phases of EVD from day 7 to day 26 after symptom onset, as well as in asymptomatic mothers (table). Data on long-term presence in breastmilk is limited and inconclusive. There was some discordance between Ebola virus in blood and breastmilk in two cases (cases 3 and 4), and possibly in a third case (case 5), indicating that Ebola virus blood negativity is not sufficient to ensure safe breastfeeding in asymptomatic or convalescent mothers. Similarly, the current recommendation of testing breastmilk only in mothers who are known EVD survivors might be insufficient because asymptomatic lactating mothers in households affected by EVD have also been shown to have Ebola virus positive breastmilk.

In DR Congo, current guidance on breastfeeding issued by the Ministry of Health and supported by UNICEF recommends that in EVD-affected households, mothers and infants who have symptoms but are Ebola virus blood negative should continue breastfeeding. We are concerned about these guidelines because Ebola virus blood negativity does not necessarily equal safe breastmilk. Health practitioners and policy makers are in desperate need of more information on EVD and breastmilk. We call for systematic research on: (1) the Ebola virus appearance and duration in breastmilk; (2) the transmissibility through breastmilk, taking into account the effect of factors such as infant saliva on the virus;2 and (3) the provision of evidencebased advice for asymptomatic lactating mothers in EVD-affected households.

The repercussions of a lack of clarity on these questions are potentially enormous for DR Congo. If breastfeeding is wrongly discouraged, years of public health efforts to promote breastfeeding could be lost. Conversely, if breastfeeding is wrongly encouraged, many infants could be put at risk. It is time to give as much attention to Ebola virus in breastmilk as we do in semen.