hiv1MEET INONGE:

Inonge Siamalambo is a primary school teacher. Two years ago, when pregnant with her second child, she visited Lusaka's Chelstone Clinic for prenatal care. A routine test showed that she was living with HIV.

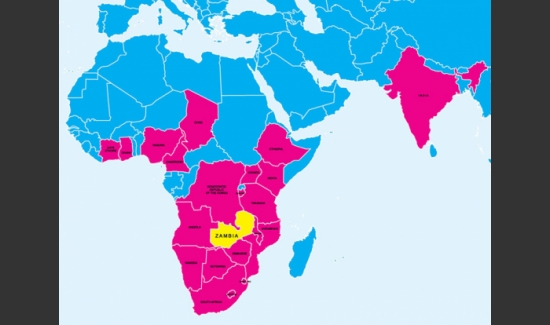

In 2008, throughout Zambia, 64 percent of prenatal clinics provided HIV testing and medicine to pregnant women living with the virus and their families. Chelstone Clinic was among them. Siamalambo began treatment there while pregnant to reduce her baby's risk of acquiring HIV.

An HIV test at the first prenatal visit is essential to protect the health of women and their babies. It becomes difficult to prevent transmission nearer birth, says Laurie Garrett, a global health researcher at the Council on Foreign Relations. In 2009, however, fewer than a third of pregnant women in the developing world were tested for the virus.

UNICEF/James Nesbitt

hiv2MEET ELSON:

In this photo, midwife Esther Chimembe weighs Elson after his birth at the Chelstone Clinic. Siamalambo underwent treatment with antiretroviral pharmaceuticals prior to delivery to maintain her health and prevent transmission of HIV to her infant.

Unlike Siamalambo, many women in low- and middle-income countries give birth at home. UNICEF is working to ensure health care providers attend more births, regardless of where they occur, so untested mothers can get checked for HIV, says Jimmy Kolker, UNICEF's chief of HIV and AIDS.

UNICEF/James Nesbitt

hiv4ELSON STARTS TREATMENT:

A nurse counseled Siamalambo on how to administer the antiretroviral medicines to Elson that should protect him from HIV. Now, medicines can reduce an infant's risk of contracting HIV from breast milk from 9.5 percent to 5.4 percent, according to the World Health Organization. Without antiretroviral treatment, about 11 percent of infants contract HIV from breast-feeding, according to UNICEF.

Siamalambo fed her son only with breast milk—the best food for a newborn—until he was six months old. In the past, mother-to-child transmission prevention programs asked all mothers to feed their babies with formula, but researchers found that practice can put infants in danger of fatal diarrhea if the available drinking water isn't clean.

UNICEF/James Nesbitt

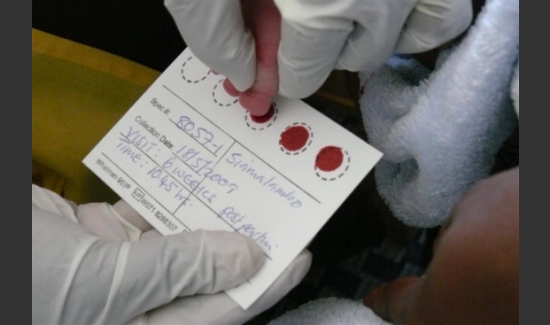

hiv5FIRST TEST:

After six weeks, Elson was due for his first HIV check. A nurse took blood samples from Elson's toe for an Early Infant Diagnosis (EID) test, which uses a technology that can detect DNA that the virus creates after it enters human cells. In 2009 only 6 percent of babies in the developing world born to mothers living with HIV received this test. Getting more six-week-olds tested for HIV is one of the greatest challenges UNICEF faces in reaching its 2015 goal, Kolker says.

UNICEF/James Nesbitt

hiv7BACK TO WORK:

By the time Elson was six months old, Siamalambo returned to her job as a teacher in a local primary school. She continued to take antiretroviral drugs, both for her own health and to minimize the risk of transmitting HIV to Elson during breast-feeding. Elson also started eating some solid food, according to World Health Organization protocols for reducing HIV transmission to children.

UNICEF/James Nesbitt

hiv9FINAL CHECK NEEDED:

Here, Siamalambo tends her vegetable garden while 18-month-old Elson looks on. Babies who have been breast-fed should receive a final HIV test one month after they are fully weaned. By the time Elson was 18 months old, Siamalambo had weaned him completely.

UNICEF/James Nesbitt

hiv11WHAT'S NEXT:

As some of the previous statistics have hinted, not all mothers finish their local transmission prevention program like Siamalambo and Elson did. The top reasons why include clinics running out of supplies and the distance some rural women must travel to get to a clinic. A trip to a city clinic may take hours by bus and require an hours-long wait to see a provider or receive test results, Garrett says. A mother with other children often cannot leave her kids for the day or more that is needed. Widespread adoption of instant testing technology would help, she adds.

UNICEF is working on improving supplies and getting their prevention program to rural clinics, Kolker says.

In some cultures, the stigma of having HIV also keeps people from getting tested and treated. Even in the U.S., where supply and distance are not an issue, a quarter of people with HIV do not know their status. "The stigma issues and the denial issues are very powerful," Garrett says.

UNICEF/James Nesbitt

hiv12BEYOND THE PROGRAM:

A 21-month-old Elson shows off pictures from the UNICEF photography project that followed him and his mother during their transmission-prevention program.

Just expanding the prevention program that protected Elson will not be enough to eliminate mother-to-child transmission, Kolker says. Women living with HIV in low- and middle-income countries need access to better family planning. Governments and organizations also need to work to prevent new HIV infections in young women. Garrett is particularly excited about a vaginal microbicide developed last year that was 39 percent effective. "If we can improve on that," she says, "we can dramatically reduce the number of HIV-positive pregnant women."

To stop the spread of the virus and treat everyone who is already sick, the effort against HIV and AIDS in low- and middle-income countries needs two to three times more funding than the $15.5 billion that's currently being spent, she argued in an interview published in June. Cleaning up fraud and reconsidering the roles of major organizations—such as the World Health Organization and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria—will free up more funds, she says.

UNICEF/James Nesbitt

Is it possible? The United Nations agency thinks so. To see why, follow an HIV-positive mom and her baby as they go through an 18-month HIV-transmission prevention program

Slideshow created by Francie Diep for Scientific American