Infections remain a leading cause of newborn deaths globally. In 2015, WHO issued a guideline for managing possible serious bacterial infection (PSBI) in young infants (0-59 days) using simplified antibiotic regimens – including fewer injections, provided closer to the community – when compliance with hospital referral is not feasible. The guideline aims to increase treatment coverage for newborn infection through provision of care that is more acceptable, accessible, and affordable for families.

Implementation research provides an opportunity to learn ‘how’ and ‘why’ interventions work (or do not work) in the real world, aiming to bridge the gap between evidence and practice. To inform operationalization of the new guideline, WHO coordinated implementation research studies in multiple countries across South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa– Bangladesh, Pakistan, India, Nigeria, Malawi, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Ethiopia. Study protocols were harmonized across the study sites, but technical support varied based on the local context.

From global guidance to national policy and implementation

In 2013, the Government of Bangladesh reinforced its commitment to ending preventable child deaths by 2035 through the A Promise Renewed declaration. This commitment called for scale-up of evidence-based newborn and child health interventions, including prevention and timely treatment of newborn infection. Bangladesh adopted the WHO recommendation of simplified antibiotic treatment for sick young infants presenting with signs of PSBI at primary health centers when referral was not feasible. To learn how best to implement this recommendation, a USAID-funded implementation research study was undertaken from July 2015 to August 2016 in three different districts of Bangladesh. This study, led by the government of Bangladesh and Ministry of Health & Family Welfare (MOHFW), was conducted in collaboration with a multidisciplinary team of stakeholders in rural outpatient health centers.

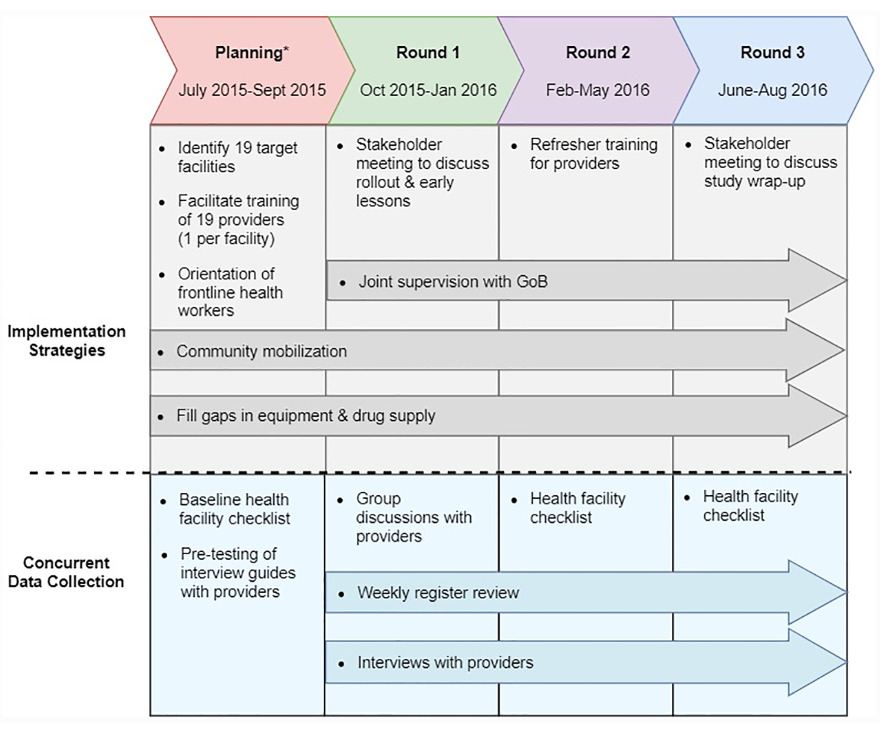

The aim of the study was to learn about the feasibility, fidelity, and acceptability of the intervention through an embedded mixed-methods evaluation, which included data collection with providers in the 19 targeted facilities and caregivers in the catchment area communities. The figure below illustrates the implementation study design:

Study findings highlighted the importance of strong government leadership and health system readiness for successful implementation of the guideline. Trained, supervised, and motivated health care providers and essential medicines and supplies need to be in place to deliver life-saving interventions. Clinical supervision and mentoring were found to be important drivers for guideline adherence. For instance, small group mentoring sessions were critical for identifying barriers to implementation and developing context-specific solutions.

Few of the expected number of PSBI cases (< 20%) sought care from the targeted health centers. When asked about caregivers’ decision to seek care, both providers and caregivers reported families often sought care from the private sector, especially informal providers near their homes. For families seeking care from study area facilities, only 16.7% of PSBI cases accepted referral to the hospital for continued care. Poor quality of care at the hospital was frequently cited as a barrier to referral acceptance. Rather, providers and caregivers reported outpatient treatment with fewer injections and oral antibiotics was more affordable and acceptable than inpatient care. However, low coverage of the intervention remains a concern in Bangladesh and efforts to improve quality of care in public-sector facilities should continue to be prioritized.

In conclusion, multi-stakeholder collaboration contributed to the successful implementation of the study and to the generation of key lessons for scale-up of implementation. Few caregivers accepted referral to the sub-district hospital, suggesting low acceptability of this option and reinforcing the value of simplified antibiotic treatment for continued care. Since the conclusion of the study, the MOHFW has incorporated plans (MOHFW, 2017) for training providers and ensuring availability of medicines and other supplies for infection management. In 2019, the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) guideline was updated to include management of sick young infants with PSBI when referral is not feasible. Efforts to strengthen the quality of care in public-sector facilities and exploration of opportunities to engage the private sector in PSBI management are ongoing.